NAND Flash: How It Breaks

Introduction

After an epic, four-post streak of device physics, silicon architecture, and standards bodies, we can finally get into failure modes.

Oh, sorry - did I say “failure modes”? I meant fun stuff. Because I can finally get rid of the dry, professorial topics and start talking about the real goods.

You heard it, folks. Today’s post is about how NAND breaks.

##Better to Burn Out than Fade Away? One of the most common errors in NAND Flash is a simple retention error. Over time, electrons trapped within the NAND array will sometimes escape. In great enough numbers, this can change the read state of the affected cell, switching a zero to a one during a page read operation. A failure like this is known as a retention error, and is generally the most common NAND Flash failure mode. The likelihood of retention errors can be exacerbated by physical effects to the device - high temperatures in particular can increase the rate at which electrons escape. There isn’t a lot we can do to prevent retention errors. All charges in all NAND cells will eventually dissipate due to entropy. The good news is that this process takes somewhere in the range of years to decades to occur. Also working in our favor is the fact that most retention errors aren’t permanent - after an erase, those same cells can generally be reused without further issues.

Slightly more serious than a simple retention error is when NAND Flash cells break down entirely. This is generally due to oxide degradation around the floating gate. We know by now that the floating gate is critical to a NAND system, and depends on its electrical isolation to function properly. These types of errors aren’t as forgiving as retention errors. When a floating gate’s electrical isolation is broken, the cell can’t store a charge any longer. This renders that bit functionally useless. Common practice is to stop using a block with a bad bit in it, but that’s a story for another day - bad block management is a complex enough subject to deserve its own post. (Stay tuned!)

I Find Your Lack of Faith Disturbing…

You may remember this diagram, from a post or two back:

Forcing electrons into isolated conductors through tunnelling (Courtesy of EETimes)

You probably also remember this diagram from the previous post:

Schematic View of NAND Array (Courtesy of InTech)

These two diagrams sum up how to program NAND - by widening the voltage gap between the word line and bit line, electrons are forced to tunnel. This works great for programming the cell that lies at the junction of the bit line and word line. It also works marginally well for programming neighboring cells, even though that isn’t intended. Why?

Take a look at the first diagram again - in particular, the graphs on the right of the image showing energy distributions. Voltage itself isn’t what determines whether electrons tunnel or not. Instead, the electric field is what determines an electron’s probability of tunnelling. It turns out that the electric field at the intersection of word line and bit line is reasonably similar to that of a charged capacitor during programming.

Electric Field Surrounding Charged Capacitor (Courtesy of Harvard)

Notice the field diagram in the image. Most of the field is contained between the capacitor’s two plates, but some of it is spilling out to the sides. In a NAND array, that’s a big deal; due to the dense packing of floating gates, the spillover from this field can cause tunnelling to occur in cells near the intended programming page.

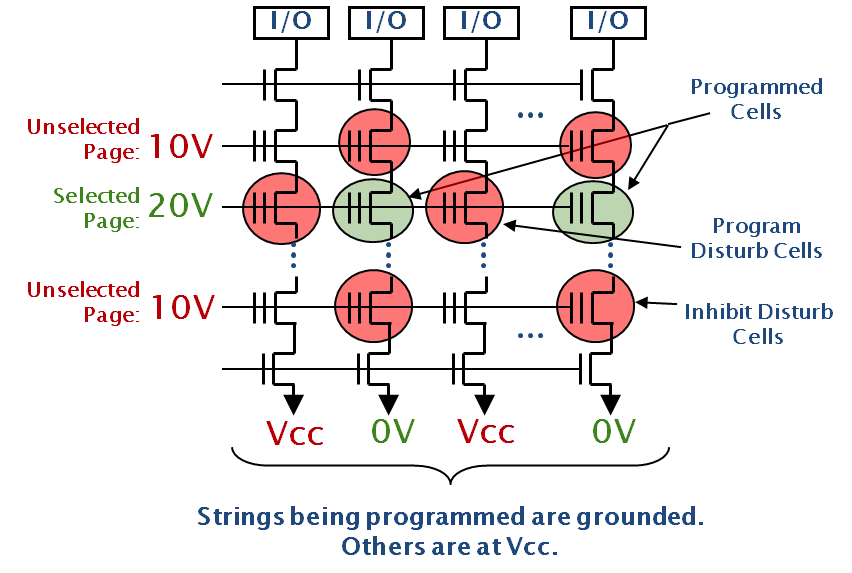

Program Disturb (Courtesy of Micron)

When enough electrons are forced into a neighboring cell during a program, that cell will appear as weakly programmed in the next page read of that cell’s page. This phenomenon is called a program disturb, and is effectively impossible to prevent in NAND. Why? The simple answer is variability, although that variability compounds from a number of different sources. A major source of this variability is directly tied to the method of programming. Since NAND Flash’s theory of operation is based on tunnelling, it’s based on a quantum effect, which means that it is probabilistic. In other words, we can’t guarantee that we’ve fully charged a floating gate to the point that it will read out as a zero during the next page read. The controller can maintain the bit line/word line voltage for long enough that there is a good chance that the cell is programmed, but it’s not 100% certain that NAND is programmed. As it so happens, the converse is also true: we can’t guarantee that we haven’t accidentally programmed neighboring cells. The right set of conditions can send electrons hurtling into neighboring floating gates completely unintentionally.

Compounding this probabilistic effect are the natural variations in silicon manufacturing. Even with today’s high tech fabrication processes, transistors and other electrical structures manage to have some natural discrepancies in their shapes and sizes. Differences in the floating gate and other transistor layers have a marked effect on disturb rejection. Thinner oxide layers, for example, mean that fewer electrons trapped in the floating gate can result in a read where none was intended. In the early days of NAND Flash, this level of variation is almost meaningless - silicon structures were too big, and energy levels too high, for a few stray electrons to have much of an effect. Shrinking die sizes have changed this drastically; today, vendors’ most modern chips have silicon feature sizes so small that the difference between a one and a zero in a NAND cell is in the hundreds of electrons. This low margin of error is compounded by the fact that the NAND connection to ground isn’t being read directly during a page read. Instead of waiting for the bit line to be pulled completely to ground, silicon vendors instead implement a simple differential amplifier to sense a change in voltage on the bit line. This means that minute changes in the floating-gate transistors’ impedances (for example - by some stray, tunnelled electrons) can be amplified and mistaken for programmed bits.

It’s worth noting that there’s a complimentary effect to program disturb. Known as a read disturb, the mechanism is effectively the same as a program disturb, except for the fact that it happens on a page read operation rather than a page program. Read disturbs are slightly less likely to occur than program disturbs due to the lower voltage differential required to read as compared to programming.

Review and Wrapup

There are a ton of possible ways for NAND Flash to go south on you. By this point in the article, any sane engineer would be wondering “Why do we even bother using it at all?” An excellent question! The simplest answer comes down to one of the most powerful forces in the universe: price. NAND Flash is cheap - in fact, in terms of cost per bit, it is one of the cheapest memory technologies on the market. As of this piece’s publication, DRAMExchange lists the price of a 4Gb DDR3 DRAM chip at an average of ~$2.02. For approximately the same price (slightly less, in fact), you can purchase an MLC NAND Flash device with 32Gb of storage space, or eight times the capacity of the DRAM.

Is the almighty dollar not telling you a compelling enough story about NAND? Don’t sweat it - as it turns out, there are ways of dealing with NAND’s physical shortcomings. The next post will go over a few of the most commonly used techniques.

Further Reading

Though not directly related to the topic at hand, I highly recommend checking out DRAMExchange, a stock exchange type site that tracks the market prices sfor semiconductor memory. It really serves to highlight how standardization has commoditized semiconductor memory.

For a more complete overview of how NAND breaks, I would recommend the following presentation, “The Inconvenient Truths of NAND Flash”, written by Jim Cooke from Micron Technology. It’s an excellent summary of NAND failure modes, as well as a small preview into our next post.